Originally, I hadn’t intended to cover Boudica – she’s a familiar figure to many, and I want this blog to focus on more obscure-yet-awesome ladies. However, I received this request through the Suggestion Box, so here we are!

Unfortunately, all we know of Boudica comes from Roman authors writing decades after the fact, so expect a lot of reading between the lines on this one.

Her name means ‘victory’ in Celtic, and has been spelled alternately as Bouddiccea or Boadicea. It’s possible Boudica may not even be the name she was born with – perhaps she only assumed the name after declaring war on the Romans. We’re also unsure when Boudica was born; only that she died in 61 C.E. with two adult daughters.

Her name means ‘victory’ in Celtic, and has been spelled alternately as Bouddiccea or Boadicea. It’s possible Boudica may not even be the name she was born with – perhaps she only assumed the name after declaring war on the Romans. We’re also unsure when Boudica was born; only that she died in 61 C.E. with two adult daughters.

Boudica came from a culture far more woman-friendly than the Romans. Some Roman writers have expressed shock at the sexual licentiousness of Celtic women; which I personally interpret to mean that Briton women enjoyed a higher degree of sexual freedom. And sexual freedom for women often correlates to more economic and political power in their hands. Celtic women were taught how to fight (and, judging by recently uncovered graves, some made a career out of it), so Boudica likely knew how to use a sword and drive a chariot by the time she reached adulthood.

At some point, she married an Iceni king, Prasutagus (the Iceni were a sub-culture of Celtic Britain, settling mainly the eastern coast of England now known as Norfolk). We don’t know how many children Boudica had in total, but two daughters survived into adulthood.

According to the historian Cassius Dio, Boudica was a tall woman with a husky voice and wild, red hair down to her hips. She wore a multicolored dress (possibly an early version of plaid), a thick mantle and a large gold torc (a necklace which was the Celtic equivalent of a crown).

We don’t know anything about her marriage to Prasutagus, though likely she enjoyed some measure of power in her own right. And though much of what happened in 60 and 61 C.E. was squabbling over Prasutagus’ property after his death, some of the disputed property may have been hers.

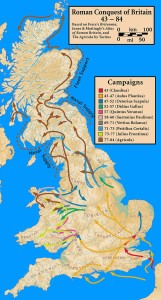

After a semi-failed rebellion in 43 C.E., Prasutagus and Boudica agreed that the Iceni would become a client kingdom of Rome. During Prasutagus’ life, he could retain all his power and property (though still had to pay tribute to Rome). Upon his death, Iceni territory would become a Roman civitas and officially join the Empire. However, Prasutagus, in his will, attempted to give half his property to Boudica – likely an attempt to make sure his widow and children were cared for after his death. However, the Romans disagreed, and refused to honor his will.

To exacerbate matters, the Roman governor of Britain, Suetonius, was currently occupied burning down the sacred Druid groves on the isle of Mona, and killing any Druid he could catch. As the Druids were the spiritual leaders of the British Celts, and the groves of Mona tantamount to the Vatican, the Britons understandably felt horrified and outraged by what Suetonius had done.

After Boudica found herself a widow, the Romans moved in like a swarm of locusts. They seized all of Prasutagus’ property, and demanded immediate repayment of the late king’s considerable debts. Steep taxes were levied, and Iceni nobles were reduced to slavery (the peasantry and other slaves probably fared poorly, too). Boudica, no doubt grieving her husband, traveled with her daughters to the local Roman magistrate and petitioned him for leniency.

After Boudica found herself a widow, the Romans moved in like a swarm of locusts. They seized all of Prasutagus’ property, and demanded immediate repayment of the late king’s considerable debts. Steep taxes were levied, and Iceni nobles were reduced to slavery (the peasantry and other slaves probably fared poorly, too). Boudica, no doubt grieving her husband, traveled with her daughters to the local Roman magistrate and petitioned him for leniency.

The magistrate did not respond well.

He ordered Boudica publicly flogged, and her daughters raped.

He would later come to regret this.

See, Boudica had run out of options. Would she still have rebelled if the Romans left her alone, letting her keep her house and some income? Her husband wanted to live in peace with the Romans, and perhaps Boudica would have made the same choice. If they’d let her. But the Romans took away her wealth, and, with the rapes and beatings, the dignity of her and her surviving family. Of course Boudica would fight back – what else could she have done?

And so Boudica began building her army. She accepted anyone willing to fight the Romans – even the very old or the very young. She quickly raised over 100,000 fighters: nobles who had been dispossessed, Iceni furious at the disrespect paid their queen, and Celts who could still smell the ashes of burning Mona.

Before beginning her march, Boudica supposedly released a rabbit from her skirts as a divination. The rabbit hopped in an auspicious direction, and Boudica prayed loudly to Andraste, the Celtic goddess of victory. As a die-hard fan of a particular franchise involving another Andraste, this story fills me with glee.

The army marched first to Camulodunum, a retirement community for Roman soldiers and home to a temple which had become a symbol of Roman oppression. The residents of the city knew Boudica was on her way, and sent frantic pleas to the governor for help. But Suetonious, doubting that an army of ‘barbaric’ Celts led by a woman could pose any real threat, did not take the pleas seriously.

He should have.

Boudica and her army systematically took the city apart. Over a period of two to three days, the soldiers went street by street through the city, setting fire to civilian homes and murdering the residents (and, of course, destroying the temple). She then turned towards the new-but-thriving trade city of Londinium, and gave that city the same treatment. Her army utterly destroyed Londinium, so much that archaeologists now have a handy guideline when excavating ancient London and Camulodunum – a ruddy layer of ash and rubble, a meter thick in some places.

After wrecking two Roman cities, Boudica then moved to Verulamium and began laying siege.

According to Tacitus, Boudica killed between 70,000 and 80,000 civilians during her campaign, and he accuses the Iceni of committing various atrocities and war crimes. Tacitus certainly isn’t an unbiased resource, but, if I may quote another video game franchise, “War never changes.” Though Boudica fought to avenge the sexual violence perpetrated against her and her daughters, she nevertheless caused the deaths of many other innocent women and their families. It’s not beyond comprehension that, even if Tacitus exaggerates, the Celtic soldiers were themselves responsible for more rapes as they systematically put the people of Camulodunum to the sword (few human remains have been found in Londinium; likely the residents of that city had time to evacuate).

At Verulamium, Boudica’s army met the Romans for the final time. Suetonius, now taking her seriously, sent several Roman legions to meet her. Her army still greatly outnumbered the Romans, but it’s not for nothing that the Roman military has been acknowledged as one of the greatest war machines in human history. The Romans, taking advantage of some local geography and forcing the Britons into a bottleneck, used their superior equipment and discipline to rout Boudica’s army. Unquestionably, the Romans emerged the victors, and the survivors on the Celtic side scattered.

At Verulamium, Boudica’s army met the Romans for the final time. Suetonius, now taking her seriously, sent several Roman legions to meet her. Her army still greatly outnumbered the Romans, but it’s not for nothing that the Roman military has been acknowledged as one of the greatest war machines in human history. The Romans, taking advantage of some local geography and forcing the Britons into a bottleneck, used their superior equipment and discipline to rout Boudica’s army. Unquestionably, the Romans emerged the victors, and the survivors on the Celtic side scattered.

Boudica herself evaded capture, and her final fate remains unknown. She may have poisoned herself, or succumbed to illness or injury soon after the battle. Historians have yet to locate her grave, or even the place where she fought her last battle.

Unfortunately, Boudica ultimately failed in her goals. Generation by generation, Roman control spread across Britain, peaking in 209 and remaining that way until the fall of Rome in 410. Only Scotland (and possibly Ireland) remained free. And while some sub-groups of Celts (such as the Welsh) survived the Roman occupation with their cultural identity intact, the Iceni effectively ceased to exist as a distinct group. And the cities which Boudica attacked survive – London, of course, but Camulodunum is now known as Colchester and Verulamium as St. Alban’s.

Interestingly enough, though Roman Britons would have known Boudica’s legend, receding Roman influence after 410 meant that, throughout the medieval era, Boudica was largely forgotten. The Celtic people were superstitious about writing, and the bards who told her story would not have written it down. As such, she cannot be found in medieval histories of Britain. However, with the advent of the Renaissance and the rediscovery of Roman writers, the British became re-acquainted with her. She became a symbol of fierce British independence, and enjoyed a resurgence in popularity during the Victorian era, becoming a subject for English painters and sculptors. Currently, archaeologists working in Colchester have uncovered several valuable treasures from Boudica’s revolt!

One of the more fanciful tales about Boudica is that she lies buried between Platforms 9 and 10 of King’s Cross Station (King’s Cross itself being dubiously indicated as the site of her final battle). There’s absolutely no evidence for this assertion, and it’s likely a post-WWII fabrication. However, I prefer to think that the woman who once prayed to Andraste is buried beneath Platform 9 3/4.

As a symbol of British nationalism, Boudica appears in a long list of books, plays and films, and has been the subject of various documentaries. You can play as Boudica in Sid Meier’s Civilization IV (a good choice if you want to conquer your neighbors), and she’s even got a strand of DNA named after her. There’s also a no-sew guide to dressing up as Boudica for Halloween. A few historians doubt she ever existed at all… but there’s that meter-thick deposit of ash and ruin which indicates something happened, and it might as well have happened roughly as Tacitus and Dio said it did.

Next week!

I’m now 2 for 3 when it comes to British women. It’s time to get off the island and visit somewhere else. If you have a suggestion, leave a comment or drop me a note!

Resources

2 Comments