So, I really wanted to do another LGBT woman to continue Pride Month, but the tragic attack in South Carolina, and the realization that today is Juneteenth, made me change my mind. Instead, I want to talk about a woman of color. And instead of talking about a fighter or a soldier, I want to talk about a spy.

I haven’t covered a female spy yet; I’ve mostly focused on women who took up arms or led armies. But spies participate in war just as much as any soldier or general, and though they may not be on the front lines, they risk their lives all the same. A captured soldier may sometimes rely on being taken as a prisoner of war and later returned home; but a captured spy is generally summarily executed. And the best spies are often those we don’t find out about until long after the war.

And so.

Meet Mary Bowser.

Mary was born a slave in or around 1839 in Richmond, Virginia. I tried to find out more about her parentage, but the only thing known is that she was born to a slave owned by the hardware merchant John Van Lew. John Van Lew was a ‘soft’ abolitionist, who freed Mary and eight other slaves in his will after his death in 1843. His daughter Elizabeth, who had been educated by Quakers and had strong abolitionist beliefs as a result, went even further. She used part of the Van Lew estate to buy the freedom of the freed slaves’ families (over the objections of her brother and mother).

Mary, still a child, was retained in the Van Lew household as a servant; or, more likely, her mother was retained as a servant and Mary grew up in service (former slaves staying on as paid servants was common practice). However, Elizabeth, for reasons of her own, quickly took a special interest in young Mary. While most black Christians in Richmond received baptism at the First African Baptist Church, Mary was baptized in 1846, at St. John’s Episcopal Church, a largely white church to which Elizabeth belonged. And when Mary’s natural intelligence and quick wit shone through, Elizabeth paid for Mary to be educated at Anthony Benezet‘s school for black children in Philadelphia.

Mary studied hard, and reportedly had a near-photographic memory. She could read a page and be able to recite what was written, nearly word-perfect. After graduating in 1855, Mary was sent as a missionary to Liberia (Liberia itself was a nation founded a few decades earlier with the intention of repatriating former slaves back to Africa). However, Mary’s letters to Elizabeth reveal a deep homesickness – Africa was not for Mary, and she returned to Virginia in 1860.

There is some indication that her travel papers were not entirely in order, and Mary was arrested in Richmond under suspicion of being an escaped slave. She may even have been flogged. However, Elizabeth came to her rescue! Supposedly, Elizabeth had to claim Mary was her slave, and was made to pay a fine levied against owners who let their slaves out without a pass. Later in life, Mary would allude to having spent four months in a Richmond jail; this may be the incident she speaks of.

At some point, she met and fell in love with a man named Wilson Bowser, a free black man who also worked in the Van Lew household, and married him on April 16, 1861 – four days after the start of the Civil War. Several months later, Jefferson Davis would move the rebel capital to Richmond, and the city became overrun with Confederate soldiers, officers and politicians.

This presented a golden opportunity for both Mary and Elizabeth.

Elizabeth, using Christian charity as her shield, began to deliver food and medicine to captured Union soldiers held at Libby Prison. She also feigned several tics, such as muttering to herself and not making eye contact. As a result, many thought her insane and took less care to guard their words around ‘Crazy Bet.’

However, the greatest acts of espionage were performed by Mary.

Mary developed the persona of ‘Ellen Bond,’ a slightly dim but hard-working woman. ‘Ellen’ was brought on to help with several social events hosted by Varina Davis, wife of wealthy rebel leader Jefferson Davis. Mary performed her duties so well that she was brought on as house staff, full-time.

Yes, that’s right.

A former slave and highly educated woman was given access to the top levels of the rebel army because neither Varina nor Jefferson assumed a black female servant could read or had the intelligence to make sense of complex political or strategic conversations. This was exceptionally brave of Mary. As I mentioned above, armies are not kind to spies caught in their midst – and I seriously doubt Jefferson would have been inclined to show mercy to a black woman caught spying in his own house. Mary certainly would have known this. Her race, which had held her back all her life, presented her with one unique opportunity to be of incredible aid to the Union. And Mary took it.

Mary cleaned the Davis house, helped serve dinner and tended to various domestic tasks. And she also eavesdropped on Jefferson’s conversations with his cabinet, read his mail and generally kept her finger on the pulse of the rebel army. She would pass this information on to a baker named Thomas McNiven, who was also part of the Union spy network in Richmond. Every few days, Thomas would deliver bread to the kitchens, and Mary would take the opportunity to tell him what she had learned; intelligence which Thomas then passed on (Thomas would later write that Mary was one of his best sources of intelligence; the only other spy who came close to her in providing useful information was a prostitute named Clara; another woman underestimated by the rebels).

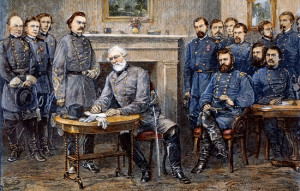

Unfortunately, Union records were destroyed to protect Mary and Elizabeth after the war, and Mary’s personal journal was lost in the 1950s. So we don’t know precisely what she told McNiven. However, according to surviving reports, some of her intelligence made its way to General Grant, and influenced his decision-making. So she definitely had an impact! I also personally suspect that every now and then, an important letter or map would mysteriously go missing from Jefferson’s office.

Jefferson eventually realized someone in his household was leaking information, but Mary played her role as the slow servant so well that she was not considered seriously as a suspect. However, her partner, Thomas McNiven, was found out sometime in late 1864 or early 1865, and Mary knew the jig was up – everyone in the household knew she frequently spoke with Thomas, and suspicion fell naturally on her. Mary got out of there as quickly as possible, but she didn’t go quietly – she attempted unsuccessfully to burn down the Davis mansion on her way out. And when the Union army re-took Richmond, Mary’s mentor Elizabeth was the first person to raise the Union colors.

From here on out, unfortunately, not much is known about Mary. Elizabeth became a near-pariah in Richmond during Reconstruction. Even though her spy activities were largely unknown to her neighbors, they nevertheless knew she had supported the Union during the war. However, Mary’s wasn’t the last life she would influence – Maggie Walker, born to black Van Lew servants in 1864, would grow up to become the first black woman to charter a bank in the United States (among a long list of other accomplishments).

Mary did go on the lecture circuit, often speaking circumspectly about her espionage during the war; and there’s some evidence she also started a school and worked to educate former slaves and their children for many years.

Unfortunately, Mary was also smart enough to know which way the wind blew in post-Reconstruction Virginia. One of her only surviving letters speaks of her fear of white anger and resentment. She picked up in many residents what she called a “quiet but bitterly expressed feeling that I know portends evil,” and doubted the black community could advance in the South without federal protection.

The date of her death and the place of her burial are sadly unknown (though rumors exist that her descendants know precisely where she’s buried, but are keeping her grave a secret to protect it).

Mary shows up every now and then in pop culture. Lois M. Leveen, a Portland-based writer, has written a non-fiction column for the New York Times, “A Black Spy in the Confederate White House,” which she later expanded into the novel The Secrets of Mary Bowser. Ted Lange wrote a play, Lady Patriot, which focuses narrowly on the relationships between Mary, Elizbeth and Varina. The play was performed in Santa Monica in 2012, to fairly good reviews. And, in 1995, her hard work was recognized when she was inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame, two years after Elizabeth.

Resources

Recollections of Thomas McNiven and his Activities in Richmond During the American Civil War