Currently in America, there’s a campaign to replace Andrew Jackson as the person featured on the $20 bill. After a first-round vote, the finalists have been narrowed down to four extraordinary women: Eleanor Roosevelt, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks and Wilma Mankiller. Rather than focus on a specific woman this week, I’d like to instead give you short vignettes on each of these four women, and draw attention to the Women on 20s campaign. The winner will get a much more in-depth biography!

Often known for being the First Lady during her husband’s administration from 1933-1945, Eleanor had quite a distinguished career of her own, focusing on civil and human rights.

Born in 1884 in New York City, she suffered immense personal tragedy early on, losing her mother at age eight and her father just two years later. She lived with her grandmother for a time, then in London while attending finishing school. The headmistress of her school was an outspoken feminist who doubtless influenced young Eleanor’s views on women and equal rights. Upon her return to America, she met Franklin Delano Roosevelt, her fifth cousin – they quickly fell in love and were married in 1905 (then-President Theodore Roosevelt gave the bride away!).

The couple had six children between 1906 and 1916, though reportedly, Eleanor enjoyed neither sex nor motherhood very much. In 1918, she discovered her husband having an affair with his secretary. And though they chose to stay together, Eleanor made it clear she would no longer sleep with Franklin. From that moment, they became a political match, and Franklin began his career in politics soon after.

In 1921, tragedy struck again as Franklin fell ill with the polio which would leave him paralyzed from the waist down. He very nearly quit politics, but Eleanor persuaded him to not give up. She became one of her husband’s most ardent supporters, doing quite a lot of campaigning on his behalf.

However, Eleanor made time to pursue her own goals while also helping Franklin. In the 1920s, her chief cause was promoting women’s rights in the workplace. She allied with the Women’s Trade Union League, which successfully campaigned for a 48-hour workweek, a minimum wage and the abolition of child labor.

In 1933, Franklin became the 32nd President of the United States of America, and Eleanor the First Lady. The role of First Lady up till then had largely been a social one – hosting dinners, parties and similar events. Eleanor, however, refused to simply be a hostess for the duration of her husband’s administration. She redefined the role as a political one, and used her time in office to campaign for the rights of the poor, as well as civil rights for African-American voters (a task she was so successful at that she single-handedly shifted the African-American voting demographic from Republican to Democrat; a trend which persists to this day).

After the White House, Eleanor served as a delegate to the United Nations, where she continued her work for human rights, assisting in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a charter universally adopted by all member nations (though several Soviet states abstained).

She died in 1962 at the age of 78.

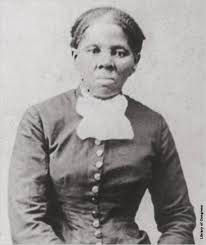

Born into slavery as Araminta ‘Minty’ Ross sometime in the early 1820s in Maryland, Harriet Tubman is most known for her work on the Underground Railroad. She witnessed early on the destruction slavery had on the family, as three of her siblings were sold away, and her mother risked her life to keep her brother.

Harriet was put to work at age 5 minding the infant of friends of her white owners, and would be whipped whenever the baby cried. Harriet would carry the scars of these beatings for the rest of her life. One beating was so bad she suffered a permanent head injury, causing her lifelong bouts of narcolepsy, epilepsy, seizures and hallucinations.

Around 1844, she married a free black man, John Tubman. Somewhere around this time, she also changed her name for Araminta to Harriet (possibly to honor her mother, also named Harriet). However, the couple lived in fear of Harriet being sold away; or of their children being enslaved. In 1849, this threatened to become a reality when Harriet’s owner tried to sell her. Only his lack of success in finding a buyer and sudden death prevented the sale. However, her owner’s widow began selling many of the household slaves, and Harriet knew it was now or never.

After one unsuccessful attempt to escape with two of her brothers, Harriet escaped on her own. Aided by conductors on the Underground Railroad, Harriet eventually made it to safety and freedom in the Northern states.

However, Harriet could not forget those she left behind, and soon made plans to return in order to liberate more loved ones from slavery. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 meant slave-hunters could capture escaped slaves even in Northern states, and so Harriet extended her route to Canada.

All told, she rescued approximately seventy slaves. She was never caught, nor were any of her charges. She also provided a great deal of support to other escaping slaves, giving them advice and guidance. She ran her last trip in December, 1860.

During the Civil War, Harriet tirelessly supported the Union Army, working as a spy, scout and even once personally leading a military attack on a group of Maryland plantations. The raid was a success – the Union forces seized several thousand dollars’ worth of supplies, and over 750 slaves were liberated. She was also a voice in Lincoln’s ear, convincing him to allow black men to enlist, counsel he eventually took. Despite all her work, Tubman was never fairly paid by the government for what she had done.

After the war, Harriet worked various odd jobs, and in 1869, she married Civil War veteran Nelson Davis. However, they were often in financial difficulty, and survived due to community donations (including sale of a biography about her). She dedicated much of her time after the war to the cause of women’s suffrage, including suffrage for black women.

She died in 1913.

Though America lost Harriet Tubman in 1913, we gained Rosa Parks on February 4 of that same year. She grew up on a farm in Alabama with her mother, her maternal grandparents and several siblings. She attended several schools, but was forced to cut her education short when both her mother and grandmother fell ill and required Rosa to care for them.

She grew up in a Jim Crow climate, where she regularly witnessed white children being bused to much nicer schools than hers; her school was twice attacked by arsonists, and the KKK would march through her neighborhood. And though white bullies would sometimes attack Rosa, she would never back down, and would often (dangerously) fight back.

She married Raymond Parks in 1932, who was a card-carrying member of the NAACP. She finished high school in 1933, becoming part of the 7% of African-Americans at the time who successfully did so. However, she could not find suitable work, and often worked unstable employment as a domestic servant. In 1943, she, too became active in the NAACP. At one meeting of the Montgomery chapter, she became elected secretary by virtue of being the only woman in the room. However, she proved to be quite good, serving in this role until 1957.

In 1944, a young black woman was gang-raped by white men, and Rosa spearheaded a successful campaigns to get justice for Recy Taylor, the survivor.

As the Civil Rights movement gained momentum, one of the issues which Rosa’s local NAACP chapter paid attention to was the segregation of the bus system, and decided to protest the unfair rules.

Some narratives have Rosa too tired to move at the end of a long work day. And while Rosa was tired, she was more tired of injustice. Her refusal to move was a deliberately calculated move to force the bus driver to enforce these unfair rules on her (thereby bringing attention to the injustice). This he did, having Rosa arrested and taken to jail.

She was bailed out the next morning, but the Montgomery Bus Boycott had begun. Rosa was eventually convicted of violating the municipal segregation laws, and charged $14 in fines. This, she refused to pay, and appealed her case. A young reverend, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., then a relative unknown, rose to prominence leading the 381-day boycott of the Montgomery bus system. The boycott eventually ended when the Supreme Court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that these laws were unconstitutional.

Though Rosa had by now become a symbol for the Civil Rights movement, that very notoriety made her (and her husband) unemployable. She eventually moved north to Detroit, where she found a system of segregation that, while not official and legal, was no less insidious. However, she provided crucial assistance to John Conyers, then running for Congress. Upon Conyers’ election, Rosa was hired as his secretary, a job she would hold until 1988.

Rosa’s new cause was housing fairness, as she saw how housing inequality and ‘urban renewal’ programs disparately affected blacks and other people of color. She worked for this cause, and many others, until her health eventually declined to the point where that became impossible.

She passed away in 2005.

Perhaps the least well-known woman on this list, I personally can think of no better person to replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill.

She was born in 1945 in Talequah, on Cherokee Nation land in Oklahoma. Her father was a full-blooded Cherokee and her mother Dutch-Irish who nevertheless adopted Cherokee customs and lived in Talequah with her family.

Her father was extremely poor, relying on a small patch of land to survive. However, this land was seized by the US Government (along with the land of 45 other Cherokee families) to expand Fort Gruber. In 1956, the family left Oklahoma and settled in San Francisco.

She married at age 17, to an Ecuadorian college student named Hector Hugo Alaya de Bardi, and had two children with him. She attended Skyline College, then San Francisco State University, finally graduating with a degree in social sciences from Flaming Rainbow University in Oklahoma.

In 1969, she participated in the occupation of Alcatraz Island, a year-long protest meant to call attention the seizure of Native lands. The protest had a solid legal footing – several treaties guaranteed that unoccupied federal land belonged to the Native tribes, and Alcatraz had not operated as a federal prison for six years. Unfortunately, Wilma and her companions did not succeed, as they were eventually forcibly removed by government agents.

However, Wilma did not let this failure dull her activist spirit. She became dedicated to the idea of helping her people.

In 1977, she divorced Hugo and moved back to the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. In 1983, she was elected deputy chief of the Cherokee Nation, and inherited the role of principal chief when her counterpart took a job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She was elected principal chief in her own right in 1987, and served until 1995 (she is often credited with being the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation… though it’s doubtless that some of her female ancestors may have also served in similar leadership roles, as Cherokee culture has a long tradition of female leadership).

During her tenure, Wilma was dedicated to improving life for residents of the Cherokee Nation. She worked closely with other community leaders, as well as the United States government, on a variety of programs meant to foster community involvement. She completely redefined tribal relationships with the US government, founded schools, improved tribal health care and increased tribal enrollment to nearly three times what it had been. Her work was not without controversy, but she can be fairly said to have made all her choices with an eye towards making life better for her people.

She married again in 1986, to a full-blooded Cherokee named Charlie Lee Soap; where they lived on Wilma’s ancestral land (the acreage taken several decades before by the government).

In 2010 (after already suffering bouts of myasthenia gravis, a kidney transplant, lymphoma and breast cancer), Wilma was diagnosed with the disease that would kill her – pancreatic cancer. She died in April of that year, leaving behind not only the legacy of a leader who broke gender barriers, but as a symbol of Native resilience in the face of attempted genocide. In 1830, then-President Andrew Jackson worked very hard to pass the Indian Relocation Act, by which the settled tribes of the American South, among them the Cherokee, were to be forcibly relocated east of the Mississipi. This eventually led to the Trail of Tears, in which 4,000 people died during a 21-day forced march from Tennessee to Oklahoma. And yet the Cherokee, as a people, survived. As such, I think it more than fitting for Jackson to lose his place on our money and for Wilma Mankiller to replace him.

However, all four of these ladies are extraordinary, and I encourage you to visit Women on 20s and vote for your personal favorite!