Welcome to Amazon Month, Week 3!

Today, we’re going to talk about a group of women often referred as the ‘Dahomey Amazons.’

As hard as I tried, I could not find the personal history of any of the Dahomey Amazons, and found only one or two names. So I’m going to depart a little bit from the format of this blog, and talk about a group of women rather than an individual woman.

The Fon are an ethnic group of Africans, living mostly in what is now Benin and Nigeria (the coastal region along the southwestern curve of Africa). In or around 1600, a Fon leader founded what would eventually become known as the Kingdom of Dahomey. Being situated on the western coast of Africa, Dahomey was uniquely positioned to deal with European slavers. And this they did, becoming both fabulously wealthy and deeply resented by the neighboring African kingdoms.

To meet the demand for slaves, Dahomey developed both a martial culture and an economy largely based on fighting other nations, kidnapping civilians and then selling them to Portuguese, Dutch or English slavers (The fact that Africans participated in the slave trade should in no way be taken as an excuse for slavery as a whole. There’s no justification for slavery, and readers should keep in mind that, as awesome as the Dahomey Amazons were, their lifestyle was made possible by slavery).

Originally, the Dahomey Amazons were called the gbeto, and were dedicated not to war, but instead to hunting elephants. According to legend, they were complimented by King Agaja after a particularly successful hunt; wherein the commander of the gbeto said she appreciated the compliment, but would much rather hunt the most dangerous game. The king was so impressed by both her talent and her boldness that he agreed.

At first, the gbeto worked as palace guards and the personal protectors of the king. Many places in the royal compound were off-limits to men after nightfall, but the gbeto could come and go as they pleased. Around 1708, as the Dahomey military underwent a general expansion, the gbeto evolved into a woman-only squad of crack fighters.

At this point, I have to point out, as I often do on this blog, that much of what we know about the Dahomey doesn’t come from these women themselves, but rather from fascinated European traders and missionaries who wrote about their African travels. The parallels between these women and the classical Amazons were obvious to a 17th century European, and so they are often known as the Dahomey Amazons. However, that’s not what they called themselves. A woman who fought for the King of Dahomey called herself a Mino (a Fon word meaning ‘our mothers’ or ‘my mother’), and so that is the word I’ll use from now on.

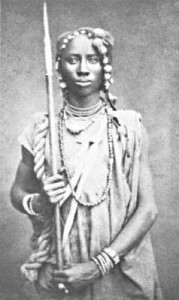

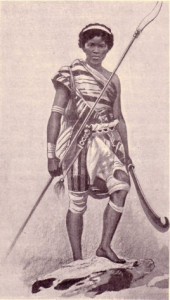

Mino fought with a variety of weapons, but the most common were the spear, the musket and the machete. These weren’t the basic machetes you can find in a home and garden store – Mino machetes were reported to be three feet long, razor-sharp and required both hands to wield.

The Mino recruited from all quarters – capable-looking women taken in slave raids could become Mino rather than being sold, and a Dahomey man upset with a headstrong wife or daughter could also send her to the Mino. Some of these headstrong women probably headed their fathers or husbands off at the pass, and went off to join the Mino of their own accord. For their part, the Mino didn’t really care – if you were a woman, if you were strong and if you were willing to fight to the absolute death, they’d take you.

Part of the joining rite for the Mino was a symbolic wedding to the Dahomey king. As a result, the Mino were forbidden to have children or marry another man (if caught with a lover, both of them were destined for a very quick execution). If we take the words of the European men who wrote about them at face value, the majority of the Mino were virgins, but I personally call shenanigans on that. The Mino weren’t a small squad of hand-picked women; at their height, they were thousands. Doubtless most Mino obeyed the order to not have children, but I can’t believe they weren’t as randy as any other group of soldiers. Get six thousand women in an army together, at least a few of them are going to come up with a few creative ways to enjoy sex without risking pregnancy.

It should be noted that the actual joining rite for the Mino has since been lost to history; but the symbolic marriage aspect and the vows to which the Mino were beholden was something generally known. As such, I feel safe in assuming that, whatever else happened when a young woman became one of the Mino, a symbolic wedding was part of it. As this tradition developed, the Mino also became known as ahosi, meaning ‘king’s wives’ (though the word ‘ahosi‘ in specific can sometimes mean anyone in direct service to the king).

Mino training was not easy, and started as young as eight years old. The Mino understood they would constantly be judged against their male counterparts, and were absolutely determined to surpass them in every way. The Mino were disciplined, rigorous, and brutal. Part of their training exercises consisted of giving weapons to captured enemies, and then literally hunting them through the jungle. To the bloody death. Barefoot.

One missionary describes watching an exhibition, in which a group of fearless Mino run across thorns (still barefoot) and engage in a mock battle. The winning women were given thorn belts, which they wore proudly and with no outward sign of pain. Other writers describe watching teenage Mino recruits perform executions, an exercise intended to desensitize them to violence and killing.

Though the demands of Mino life were difficult, the benefits often made up for it. Mino women were wealthy, sharing in the spoils of war and receiving payment for their service in gold, tobacco, alcohol and even an allotment of slaves. A Mino could walk proudly down the street and expect everyone to get out of her path. Even touching a Mino was dangerous – if she didn’t kill you herself, you may very well face execution for your temerity.

The Mino motto was Conquer or Die, and they meant it. Only the king himself could order a Mino to retreat from battle; if she ran from the front lines for any other reason, she would be summarily executed by one of her sisters on the spot.

Though some have interpreted the existence of the Mino to indicate that Dahomey culture was markedly gender equitable, other evidence suggests this might not be entirely the case. Dahomey society still had strict gender divisions. Though the Mino enjoyed a high social status, they were forbidden marriage and family life (a rule not imposed on male soldiers). There is some evidence that the Mino did not even consider themselves fully female – often, the Mino would refer to themselves as men. This probably isn’t an indication that the Mino should be considered transmen; but rather that the Mino took a unique approach to gender performativity.

In a nutshell, gender among the Dahomey was progressive in some ways (career options did exist for women) but regressive in others (the career options were limited, women had to choose between career and family). In this way, the Dahomey were much like any other complex society of the time; women had access to some areas but were barred from others.

It’s also important to consider the context I mentioned above: Dahomey’s economy relied on slavery. Their practice of conquer-kidnap-sell (which was something all African nations in the region engaged in at the time) meant that not only did the nation of Dahomey constantly need to protect itself from angry neighbors, the entire region dealt with the effects of male depopulation, as millions of men were sold into slavery. These unique pressures created room for the rise of the Mino.

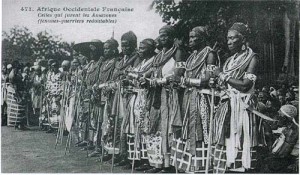

At their height, the Mino were fully half of the Dahomey military strength, and the commander of the Mino directly advised the king on which nation to conquer next.

Unfortunately, though the Mino were unmatched among the other nations of Africa, they could not compete with the military might of 19th century Europe during the Scramble for Africa. In 1890, they tangled with several French settlements. At first, the Mino won several easy victories; as the French soldiers defending the fort were not prepared and had a hard time attacking women. Eventually, however, the French remembered they had Gatling guns and cannonballs, and attacked the Mino from the safety of their gunboats. Despite their overwhelming bravery, the Mino had no hope when it came to such weapons – their military technology was significantly behind Europe’s.

However, they made the French work for it. All told, Dahomey and France would fight twenty-four battles for Dahomey territory, and only advanced French technology ensured their victory. Had the Mino and their male counterparts been able to meet their opponents with equal weapons, likely the battles would have gone far differently.

But Dahomey fell to France in 1894, and only 50 Mino, out of nearly 4,000, survived. The French even passed strict laws once they achieved control, banning women from military service or even owning weapons. The majority of those women sailed for America, where they ended up joining Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

As far as we know, the last surviving Mino, a woman named Nawi, died in 1979.

The Mino deserve a unique place in history – for though women have always fought, they’ve often done so while integrated into largely male units. Most female-only military units have been supportive, or last only for the duration of the current conflict. But the Mino existed as a distinct female military tradition of front-line fighters; something which cannot be found anywhere else (The Elk Scraper Society I mentioned in the entry for Buffalo Calf Road Woman is the only thing I’ve found which comes close).

The Mino occassionally show up in pop culture here and there (such as a unit in DLC for the the digital game Empire: Total War), but they have yet to make a significant appearance in fiction, film and TV. However, the rising school of Afro-centrist historical revisionism mentioned last week loves the Mino as much as they love Calafia; so here’s hoping these women get their own property soon!

Resources

Amazons of Black Sparta: The Warrior Women of Dahomey

From Eve to Dawn: The Masculine Mystique

Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey